Ida Lupino does her Christmas shopping circa 1939

Ida Lupino does her Christmas shopping circa 1939 For Stanley and Connie Lupino, the brightest momdnt of the war years was the birth of their daughter Ida. They had almost named her Aida, after the princess of the Verdi opera, an appropriate suggestion of theatrical royalty. Ida's sister, Rita, was born in 1921. Both children soon learned that emotions were for display; laugh, cry, speak boldly and beautifully. Emotional restraint was not for the Lupinos. Ida never had a normal childhood because of her parents' touring and late hours.

For Stanley and Connie Lupino, the brightest momdnt of the war years was the birth of their daughter Ida. They had almost named her Aida, after the princess of the Verdi opera, an appropriate suggestion of theatrical royalty. Ida's sister, Rita, was born in 1921. Both children soon learned that emotions were for display; laugh, cry, speak boldly and beautifully. Emotional restraint was not for the Lupinos. Ida never had a normal childhood because of her parents' touring and late hours. "Her self-confidence is utterly sumptuous". -Reporter Alma Whitaker about Ida Lupino

"Her self-confidence is utterly sumptuous". -Reporter Alma Whitaker about Ida Lupino  Ida Lupino in "Ready For Love" (1934)

Ida Lupino in "Ready For Love" (1934)Calling herself Ida Ray, Lupino obtained an agent and immediately landed a part. A German director who had seen her on the set of "Love Race" hired the girl with luminous blue eyes and milk-white skin. Ironically, she was dropped from her only scene for fear her attractiveness would overshadow the lead actress. After this happened several times, Ida became known as "the girl who was too good-looking." In January 1932, Ida officially enrolled in the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. Student life was crowded with activity and admirers flocked around. Ida had her first boyfriend, a fellow student named Johnny, who nicknamed her "Loops." They spent their free hours together chatting before the fire in Ida's room.

George Bernard Shaw, regarded as the greatest living playwright of the English language said of Ida: "She is the only girl in the world as mad as I am."

George Bernard Shaw, regarded as the greatest living playwright of the English language said of Ida: "She is the only girl in the world as mad as I am." Ida Lupino and Richard Arlen in "Ready For Love" (1934)

Ida Lupino and Richard Arlen in "Ready For Love" (1934) Paramount decided that Lupino's screen debut would be in "Search for Beauty", a romantic comedy about Olympic champions who became entangled with con men. Ida had a knockout scene: dressed in silk pajamas, she danced a snakehips atop a table to save voluptuous Toby Wing from a roomful of evil-minded drunks. Toby Wing became Ida's friend. She found Ida full of fun. Ida's second Paramount release was "Come on Marines", in which Richard Arlen gallantly leads an armed squad into the jungle to rescue beauties from a Paris finishing school. Ida scoffed at reports that she had come to America just to play "Alice in Wonderland". "You cannot play naive if you're not. I never had any childhood", Ida said. About her friends, she said: "I cannot tolerate fools, won't have anything to do with them. I only want to associate with brilliant people".

Paramount decided that Lupino's screen debut would be in "Search for Beauty", a romantic comedy about Olympic champions who became entangled with con men. Ida had a knockout scene: dressed in silk pajamas, she danced a snakehips atop a table to save voluptuous Toby Wing from a roomful of evil-minded drunks. Toby Wing became Ida's friend. She found Ida full of fun. Ida's second Paramount release was "Come on Marines", in which Richard Arlen gallantly leads an armed squad into the jungle to rescue beauties from a Paris finishing school. Ida scoffed at reports that she had come to America just to play "Alice in Wonderland". "You cannot play naive if you're not. I never had any childhood", Ida said. About her friends, she said: "I cannot tolerate fools, won't have anything to do with them. I only want to associate with brilliant people". Since her boyfriend Johnny's death, Ida had experienced an intense emotional emptiness.

Since her boyfriend Johnny's death, Ida had experienced an intense emotional emptiness. The initial encounter of Lupino and Hayward had produced "tangible hostility." While studying a script on the set of "Money for Speed", Ida had looked up to see a stranger watching her. When they were introduced afterward, Ida was icy. "He bored me to extinction," she later recalled. "It was strange but the dislike for each other amounted to contempt." Hayward sized her up as "just another dizzy blonde." He came to America and found success on Broadway, winning the 1934 New York Critics Award. Soon he began a film career in Hollywood.

The initial encounter of Lupino and Hayward had produced "tangible hostility." While studying a script on the set of "Money for Speed", Ida had looked up to see a stranger watching her. When they were introduced afterward, Ida was icy. "He bored me to extinction," she later recalled. "It was strange but the dislike for each other amounted to contempt." Hayward sized her up as "just another dizzy blonde." He came to America and found success on Broadway, winning the 1934 New York Critics Award. Soon he began a film career in Hollywood. On her sixteenth birthday, Howard Hughes arranged a party for her. He asked her what she wanted. "Binoculars", answered Ida. "What on earth do you want binoculars for?" "To look at the stars", she replied. Hughes gave her the most expensive pair he could find. But presents never won her heart.

On her sixteenth birthday, Howard Hughes arranged a party for her. He asked her what she wanted. "Binoculars", answered Ida. "What on earth do you want binoculars for?" "To look at the stars", she replied. Hughes gave her the most expensive pair he could find. But presents never won her heart. Ida admired the press-shy Garbo. "I am a fan. Not because she is a great actress, but because she has dared the wolves and kept her splendid isolation".

Ida admired the press-shy Garbo. "I am a fan. Not because she is a great actress, but because she has dared the wolves and kept her splendid isolation". Ida Lupino in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939)

Ida Lupino in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939)She was asked to return to Los Angeles for a dramatic role in "The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes", starring Basil Rathbone. Ida portrayed a terrified woman who comes to Holmes with a strange drawing that threatens her brother with death. Cinematographer Leon Shamroy captured the eerie atmosphere, which was enhanced by the music of Cyril J. Mockridge, who composed a haunting Inca funeral dirge. A crucial scene in which Ida weeps over the body of her slain brother was beautifully played. As she sobs, she hears the faint tones of the frightening Inca dirge, the harbinger of another murder; fear, then stark terror, sweep over her, culminating in a shrill, blood-curdling scream.

Ida Lupino in "Life Begins at Eight Thirty" (1942)

Ida Lupino in "Life Begins at Eight Thirty" (1942) Ida felt that Louis Hayward was one of the few people who truly understood her. She defined her concept of love as "blind devotion." In interviews, she said she had few illusions about life but simply followed the conscious instinct of self-preservation. But she was deeply in love with Louis Hayward. Louis was certain that his agent, Arthur Lyons, could get Ida's career moving again. Lyons had for years been the dynamo who made success stories happen. From his plush office at 356 North Camden Drive in Beverly Hills, he directed one of the most affluent artist agencies in show business. Lyons represented such stars as Jack Benny, Joan Crawford, Lucille Ball, Ray Milland, Sydney Greenstreet, John Garfield, Hedy Lamarr, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, and Eugene O'Neill.

Ida felt that Louis Hayward was one of the few people who truly understood her. She defined her concept of love as "blind devotion." In interviews, she said she had few illusions about life but simply followed the conscious instinct of self-preservation. But she was deeply in love with Louis Hayward. Louis was certain that his agent, Arthur Lyons, could get Ida's career moving again. Lyons had for years been the dynamo who made success stories happen. From his plush office at 356 North Camden Drive in Beverly Hills, he directed one of the most affluent artist agencies in show business. Lyons represented such stars as Jack Benny, Joan Crawford, Lucille Ball, Ray Milland, Sydney Greenstreet, John Garfield, Hedy Lamarr, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, and Eugene O'Neill. Lyons promptly swung into action. He sent Ida to see Harry Cohn, who ran Columbia Pictures. The tough, crude, astute boss was blunt: "You are not beautiful, Ida, but you've got a funny little pan." Ida must have winced at the comment but eagerly signed a two-picture contract. Ida's depression vanished. Louis proposed, and she accepted. On November 17, 1938, Ida became Mrs. Louis Hayward in a quiet civil ceremony held in the Santa Barbara courthouse. Their new home, discovered by accident and purchased on impulse, was at 1766 Westridge in Brentwood.

Lyons promptly swung into action. He sent Ida to see Harry Cohn, who ran Columbia Pictures. The tough, crude, astute boss was blunt: "You are not beautiful, Ida, but you've got a funny little pan." Ida must have winced at the comment but eagerly signed a two-picture contract. Ida's depression vanished. Louis proposed, and she accepted. On November 17, 1938, Ida became Mrs. Louis Hayward in a quiet civil ceremony held in the Santa Barbara courthouse. Their new home, discovered by accident and purchased on impulse, was at 1766 Westridge in Brentwood. Lupino was summoned to Warner's office and offered a seven-year contract. He told her she would be "another Bette Davis." Ida recognized Warner's transparent strategy. If the queen of the lot refused to do a picture or caused trouble, Lupino would be at hand. On May 3, 1940, she signed a one-year contract with Warner Bros. that permitted her to freelance elsewhere. Her salary would be two thousand dollars a week for two pictures.

Lupino was summoned to Warner's office and offered a seven-year contract. He told her she would be "another Bette Davis." Ida recognized Warner's transparent strategy. If the queen of the lot refused to do a picture or caused trouble, Lupino would be at hand. On May 3, 1940, she signed a one-year contract with Warner Bros. that permitted her to freelance elsewhere. Her salary would be two thousand dollars a week for two pictures. Publicity still of Ida Lupino and Humphrey Bogart in "They Drive by Night" (1940) directed by Raoul Walsh

Publicity still of Ida Lupino and Humphrey Bogart in "They Drive by Night" (1940) directed by Raoul Walsh "They Drive by Night" was completed in thirty-three working days, for $498,000. Even before its release, Warner Bros. knew it had a winner, thanks mainly to Ida Lupino. Hal Wallis, head of studio production, wanted her signed for a third film. On July 8, a preview was held at the Warner Theater on Hollywood Boulevard. Ida ignited the screen; she projected a fascinating blend of beauty, danger, and deceit. Variety reported that the audience had twice broken out with applause. Newsweek proclaimed, "Raft and Bogart honest men, but Lupino steals picture."

"They Drive by Night" was completed in thirty-three working days, for $498,000. Even before its release, Warner Bros. knew it had a winner, thanks mainly to Ida Lupino. Hal Wallis, head of studio production, wanted her signed for a third film. On July 8, a preview was held at the Warner Theater on Hollywood Boulevard. Ida ignited the screen; she projected a fascinating blend of beauty, danger, and deceit. Variety reported that the audience had twice broken out with applause. Newsweek proclaimed, "Raft and Bogart honest men, but Lupino steals picture." Other reviews were equally laudatory: "Miss Lupino goes crazy about as well as it can be done," noted the New York Times. The World Telegram stated that she finally had gotten the break she deserved "and the result is a performance so superb that she immediately becomes one of the screen's foremost dramatic actresses."

Other reviews were equally laudatory: "Miss Lupino goes crazy about as well as it can be done," noted the New York Times. The World Telegram stated that she finally had gotten the break she deserved "and the result is a performance so superb that she immediately becomes one of the screen's foremost dramatic actresses." Humphrey Bogart and Ida Lupino in "High Sierra" (1941) directed by Raoul Walsh

Humphrey Bogart and Ida Lupino in "High Sierra" (1941) directed by Raoul WalshMark Hellinger chose Lupino for his next film, which he described as "a great yarn." Despite the restrictive guidelines, W.R. Burnett and John Huston completed a masterful script-the simple yet compelling story of an Indiana farm boy who turns to crime. Bogart plays Roy "Mad Dog" Earle, and Ida plays Marie, a young woman picked up at a dime-a-dance joint, who begs to stay with Earle because she has nowhere else to go.

Production began August 5; the company assembled for exterior scenes at the mountain resort of Big Bear. Initially, the relationship between Lupino and Bogart was cool. As she later disclosed, "I have a way of kidding with a straight face; so has Bogie. Neither of us recognized the trait in the other".

Production began August 5; the company assembled for exterior scenes at the mountain resort of Big Bear. Initially, the relationship between Lupino and Bogart was cool. As she later disclosed, "I have a way of kidding with a straight face; so has Bogie. Neither of us recognized the trait in the other".  Matters were complicated by Mayo Methot, Bogart's wife. As the picture progressed, Ida and Bogie established an onscreen rapport and an off-camera friendship. The volatile Mrs. Bogart constantly hovered about the set, making her husband nervous. Dialogue director Irving Rapper knew why Mayo was there, as did everyone else. "Mayo was very jealous of Ida," says Rapper.

Matters were complicated by Mayo Methot, Bogart's wife. As the picture progressed, Ida and Bogie established an onscreen rapport and an off-camera friendship. The volatile Mrs. Bogart constantly hovered about the set, making her husband nervous. Dialogue director Irving Rapper knew why Mayo was there, as did everyone else. "Mayo was very jealous of Ida," says Rapper. The script called for Lupino to cry, but the tears wouldn't come. Bogart took her to the side and, glancing at director Walsh, told her: "Listen, doll, if you can't cry, just remember one thing -I'm going to take this picture away from you." Ida laughed, just as Bogart had wanted. "All right," he said, "now you're relaxed. If you can't relate it to me or the character go back to your childhood," he counseled. "Can you remember when you had to say goodbye to somebody, somebody you loved? And you thought you weren't going to see them again?" "Yes", responded Ida. "Well, think of that, baby, think of it!" Ida saw tears in his eyes. The final scene of High Sierra is powerfully moving. Marie's tears of sadness are transformed into tears of elation as she realizes that the tortured soul of Roy Earle is finally free.

The script called for Lupino to cry, but the tears wouldn't come. Bogart took her to the side and, glancing at director Walsh, told her: "Listen, doll, if you can't cry, just remember one thing -I'm going to take this picture away from you." Ida laughed, just as Bogart had wanted. "All right," he said, "now you're relaxed. If you can't relate it to me or the character go back to your childhood," he counseled. "Can you remember when you had to say goodbye to somebody, somebody you loved? And you thought you weren't going to see them again?" "Yes", responded Ida. "Well, think of that, baby, think of it!" Ida saw tears in his eyes. The final scene of High Sierra is powerfully moving. Marie's tears of sadness are transformed into tears of elation as she realizes that the tortured soul of Roy Earle is finally free. "High Sierra" was to remain one of the greatest pictures of Ida's career and quite memorable personally for her experience with Humphrey Bogart. Initially, Ida had found Bogart's pleasure in needling people upsetting, but by the film's end, she understood that he, like herself, was a person with many sides, some of them contradictory. She grew to like Bogart and never forgot his unexpected support when the tears wouldn't come. As she was to remember: "He was the most loyal, wonderful guy in the world."

"High Sierra" was to remain one of the greatest pictures of Ida's career and quite memorable personally for her experience with Humphrey Bogart. Initially, Ida had found Bogart's pleasure in needling people upsetting, but by the film's end, she understood that he, like herself, was a person with many sides, some of them contradictory. She grew to like Bogart and never forgot his unexpected support when the tears wouldn't come. As she was to remember: "He was the most loyal, wonderful guy in the world." Ida Lupino and John Garfield in "The Sea Wolf" (1941) directed by Michael Curtiz

Ida Lupino and John Garfield in "The Sea Wolf" (1941) directed by Michael Curtiz Ida rehearsed daily with co-stars Edward G. Robinson and John Garfield. Robinson considered twenty-sevenyear-old Garfield one of the best young actors he had ever encountered. Ida was also enthralled. "His real name was Julius Garfinkle. He was wonderful and I loved him. He and I were like brother and sister." She admired her new friend and the passionate political beliefs that led him to champion the economically disadvantaged. Garfield's political boldness and his cocky spirit matched Lupino's innate rebelliousness.

Ida rehearsed daily with co-stars Edward G. Robinson and John Garfield. Robinson considered twenty-sevenyear-old Garfield one of the best young actors he had ever encountered. Ida was also enthralled. "His real name was Julius Garfinkle. He was wonderful and I loved him. He and I were like brother and sister." She admired her new friend and the passionate political beliefs that led him to champion the economically disadvantaged. Garfield's political boldness and his cocky spirit matched Lupino's innate rebelliousness. As expected, Robinson, as the bestial yet intelligent Wolf Larsen, dominated the picture. "I'd rather rule in hell than be a servant in heaven," he says. One reviewer called the picture "Little Caesar at sea."

As expected, Robinson, as the bestial yet intelligent Wolf Larsen, dominated the picture. "I'd rather rule in hell than be a servant in heaven," he says. One reviewer called the picture "Little Caesar at sea."  Though overshadowed by Robinson's masterful acting, Lupino was praised as "excellent... the girl with a past. Her intelligent and forthright playing gives complete conviction to the role." Author William Saroyan was so impressed that he wrote, "Give Miss Lupino something to act in and there's a fifty-fifty chance that she will be the finest actress in the world."

Though overshadowed by Robinson's masterful acting, Lupino was praised as "excellent... the girl with a past. Her intelligent and forthright playing gives complete conviction to the role." Author William Saroyan was so impressed that he wrote, "Give Miss Lupino something to act in and there's a fifty-fifty chance that she will be the finest actress in the world." Ida could be wickedly funny herself, but she publicly acknowledged her "terrible temper," and explained that she tried to control it but found that "keeping it back sometimes upsets me." Louis discovered he could lure his wife from her black moods by laughter, but her volatile fits and evanescent rages caused slammed doors and marital scars. Ida felt more comfortable around men. The distance she kept from her fellow females masked a grave insecurity and a fear of competition. But for Ida, women, especially actresses, were a curious breed: "A woman in show business isn't honest with herself... so how can she be honest with another woman? We are all of us acting every minute of the day and night."

Ida could be wickedly funny herself, but she publicly acknowledged her "terrible temper," and explained that she tried to control it but found that "keeping it back sometimes upsets me." Louis discovered he could lure his wife from her black moods by laughter, but her volatile fits and evanescent rages caused slammed doors and marital scars. Ida felt more comfortable around men. The distance she kept from her fellow females masked a grave insecurity and a fear of competition. But for Ida, women, especially actresses, were a curious breed: "A woman in show business isn't honest with herself... so how can she be honest with another woman? We are all of us acting every minute of the day and night." “There was a certain kind of fantasy, a certain imagination that is not accepted now. The world is too small. Those were glamorous days.” ~Ann Sheridan about her time in Hollywood

“There was a certain kind of fantasy, a certain imagination that is not accepted now. The world is too small. Those were glamorous days.” ~Ann Sheridan about her time in Hollywood Ida Lupino & Ann Sheridan dancing on the set of "They Drive By Night" (From the book "Here’s Looking at You Kid: 50 Years of Fighting, Working and Dreaming at Warner Bros." by James R. Silke)

Ida Lupino & Ann Sheridan dancing on the set of "They Drive By Night" (From the book "Here’s Looking at You Kid: 50 Years of Fighting, Working and Dreaming at Warner Bros." by James R. Silke)Despite her comments, Lupino's contradictory nature brought exceptions. Ann Sheridan was always a dear chum because she was "honest, feminine and yet had masculine directness."

After fourteen months of marriage, Howard said goodbye. He was barely out the front door when Louella Parsons had the story in print: "The strangest separation of all time is that of Ida Lupino and Howard Duff... there had been no quarrel, no trouble of any kind, and Ida thought everything was going along smoothly when Howard walked out of the house. He said he was leaving and was through."

After fourteen months of marriage, Howard said goodbye. He was barely out the front door when Louella Parsons had the story in print: "The strangest separation of all time is that of Ida Lupino and Howard Duff... there had been no quarrel, no trouble of any kind, and Ida thought everything was going along smoothly when Howard walked out of the house. He said he was leaving and was through." When Barbara Stanwyck turned down the role of Stella Goodwin in "Out of the Fog", Ida jumped at it. Producer Henry Blanke asked George Raft to play the heavy, but he declined. Bogart asked for the role, but Lupino used her influence and Blanke agreed that her pal John Garfield would play the extortionist.

When Barbara Stanwyck turned down the role of Stella Goodwin in "Out of the Fog", Ida jumped at it. Producer Henry Blanke asked George Raft to play the heavy, but he declined. Bogart asked for the role, but Lupino used her influence and Blanke agreed that her pal John Garfield would play the extortionist.  Ida Lupino and John Garfield in "Out of the Fog" (1941) directed by Anatole Litvak

Ida Lupino and John Garfield in "Out of the Fog" (1941) directed by Anatole Litvak Anatole Litvak, highly regarded at Warner Bros. for such successes as "City for Conquest" and "Confessions of a Nazi Spy", would direct. Ida pored over her script, quite excited by the fine writing and drama in Shaw's play-an honest depiction of social injustice, a study of "gentle people" who are pushed so far they rise up to exterminate the aggressor. The screenplay by Robert Rossen, Jerry Wald and Robert Macaulay remained true to the play, maintaining as much realism as possible.

Anatole Litvak, highly regarded at Warner Bros. for such successes as "City for Conquest" and "Confessions of a Nazi Spy", would direct. Ida pored over her script, quite excited by the fine writing and drama in Shaw's play-an honest depiction of social injustice, a study of "gentle people" who are pushed so far they rise up to exterminate the aggressor. The screenplay by Robert Rossen, Jerry Wald and Robert Macaulay remained true to the play, maintaining as much realism as possible.  On the film's release, the publicity department proclaimed "Lupino and Garfield-Most Exciting New Screen Team!". "Out of the Fog" opened to good reviews. "A moving and thought-provoking drama... Lupino created another outstanding character in her repertoire of tragic and oblique women, etches unforgettable. John Garfield makes his satanic portrayal the essence of symbolic villainy," said Variety.

On the film's release, the publicity department proclaimed "Lupino and Garfield-Most Exciting New Screen Team!". "Out of the Fog" opened to good reviews. "A moving and thought-provoking drama... Lupino created another outstanding character in her repertoire of tragic and oblique women, etches unforgettable. John Garfield makes his satanic portrayal the essence of symbolic villainy," said Variety.  After his difficulty obtaining film work, Garfield returned to his roots, the New York stage. He was a smash in "The Big Knife", "Peer Gynt" and "Golden Boy". Garfield had sent Ida tickets to see him onstage. She arrived at his apartment with a writer friend from the New York Times for a toast before the performance. Garfield opened the door in his dressing gown. Ida was taken aback by his haggard appearance. "Hi, doll," she greeted him. "Oh, it's good to see you, Lupi." Ida introduced her escort, then Garfield prepared cocktails. "I have a little present for you, Lupi." He glanced at Ida's friend, then said: "I'm going to ask her to come into my bedroom but not for what you think." As Ida followed him, she felt uneasy. Garfield looked deathly ill, and he lacked energy and exuberance. He pointed to a basket of flowers, champagne and glasses.

After his difficulty obtaining film work, Garfield returned to his roots, the New York stage. He was a smash in "The Big Knife", "Peer Gynt" and "Golden Boy". Garfield had sent Ida tickets to see him onstage. She arrived at his apartment with a writer friend from the New York Times for a toast before the performance. Garfield opened the door in his dressing gown. Ida was taken aback by his haggard appearance. "Hi, doll," she greeted him. "Oh, it's good to see you, Lupi." Ida introduced her escort, then Garfield prepared cocktails. "I have a little present for you, Lupi." He glanced at Ida's friend, then said: "I'm going to ask her to come into my bedroom but not for what you think." As Ida followed him, she felt uneasy. Garfield looked deathly ill, and he lacked energy and exuberance. He pointed to a basket of flowers, champagne and glasses.  Ida read the note: "To my favorite sister. Sorry, I'm not going to make it tonight but I've always loved you, kid. Julie." Ida was perplexed. "What do you mean?" she asked. "I'm not going to make it tonight or any other night," answered Garfield. "I'm booked." Ida was shocked. "I'm glad you gave me a good stiff drink. Now I have a present for you. All that junk about you being a Communist has been cleared up." Ida and her friend declined to see the play, since Garfield wasn't appearing. Ida, as she had promised, returned to Garfield's place to say goodnight. She was still worried about her friend. She tapped softly at the door and found it open. The living room was dark. In his bedroom a single lamp on a nightstand fell on Garfield, propped up on pillows sleeping. "Goodnight, Johnny. We all love you," Ida whispered. He opened his eyes and thanked her. She leaned down and hugged him. "Would you mind holding my hand till I drop off?" he asked. The words sent a chill through Ida. "You bet," she told him. "I'll sit here till daylight if you want." She held his hand until he was sound asleep.

Ida read the note: "To my favorite sister. Sorry, I'm not going to make it tonight but I've always loved you, kid. Julie." Ida was perplexed. "What do you mean?" she asked. "I'm not going to make it tonight or any other night," answered Garfield. "I'm booked." Ida was shocked. "I'm glad you gave me a good stiff drink. Now I have a present for you. All that junk about you being a Communist has been cleared up." Ida and her friend declined to see the play, since Garfield wasn't appearing. Ida, as she had promised, returned to Garfield's place to say goodnight. She was still worried about her friend. She tapped softly at the door and found it open. The living room was dark. In his bedroom a single lamp on a nightstand fell on Garfield, propped up on pillows sleeping. "Goodnight, Johnny. We all love you," Ida whispered. He opened his eyes and thanked her. She leaned down and hugged him. "Would you mind holding my hand till I drop off?" he asked. The words sent a chill through Ida. "You bet," she told him. "I'll sit here till daylight if you want." She held his hand until he was sound asleep. Ida Lupino & John Garfield in "Out Of The Fog" -We Don't Believe In Pirates (Movie Clip)

-Ida Lupino (Stella): All I know is that when he talks, I feel like I'm burning. He knows it, too, and even so, he laughs, and then I get hot and cold all over, and I feel like yelling. Nothing that ever happened to me before made me feel like this.

-Ida Lupino (Stella): All I know is that when he talks, I feel like I'm burning. He knows it, too, and even so, he laughs, and then I get hot and cold all over, and I feel like yelling. Nothing that ever happened to me before made me feel like this. What lay behind the penetrating blue eyes? I was curious. She craved solitude and attention simultaneously, just as her entrancing eyes harbored both fire and ice, love and hate, brilliance and wildness. The rays of emotion she emitted were intense, like those of a revolving prism, unique and exceedingly bright. -"Ida Lupino: A Biography" by William Donati (2000)

What lay behind the penetrating blue eyes? I was curious. She craved solitude and attention simultaneously, just as her entrancing eyes harbored both fire and ice, love and hate, brilliance and wildness. The rays of emotion she emitted were intense, like those of a revolving prism, unique and exceedingly bright. -"Ida Lupino: A Biography" by William Donati (2000) Robert Ryan and Ida Lupino in "Beware My Lovely" (1952) directed by Harry Horner

Robert Ryan and Ida Lupino in "Beware My Lovely" (1952) directed by Harry HornerIda Lupino plays a pretty widow who impulsively hires a handyman (Robert Ryan) to look after her house. She soon learns Ryan is a dangerous schizophrenic, but by the time she comes to this realization she is unable to escape her house. The tension mounts apace, leading to an unexpected but quite logical finale. Produced by Lupino's then-husband Collier Young, "Beware My Lovely" was released by RKO Radio. The tension in the film is similar to what you would get in a Hitchcock film. This film is basically Robert Ryan versus Ida Lupino. These two great actors do an excellent job handling the bulk of the work. Lupino is one of the best looking old maids you will ever see and Ryan looks like his head is going to explode any minute, of course he made a living in those roles. In this role, however, Ryan is much more vulnerable than normal but just as volatile.

Ida Lupino and Robert Ryan in "On Dangerous Ground" (1952) directed by Nicholas Ray

Ida Lupino and Robert Ryan in "On Dangerous Ground" (1952) directed by Nicholas Ray"One of the loveliest of Nick Ray's movies... a harsh film noir [that] gradually shifts to an ethereal romanticism reminiscent of Frank Borzage."—Dave Kehr

Perhaps the purest expression of Ray's belief in the transformative power of love and a classic of its genre, "On Dangerous Ground" is among his most beautiful and moving works. Written by A. I. Bezzerides of "Kiss Me Deadly" fame, the film opens in the harsh urban world of noir, Bernard Herrmann's score flaying nerves as Robert Ryan's coiled cop takes to the mean streets as a semi-psychotic avenging angel ("Why do you make me do it?" the tormented Ryan screams at the latest lowlife he pummels within an inch of his life). It is hard to say what is more stirring: Ryan's forsaken aloneness or Lupino's isolate vulnerability. The daring stylistic and tonal contrasts between the film's two halves, and the theme of the difference between moral and physical sight, intensify the film's tragic irony; in the end, all ground seems dangerous. Lupino actually directed some scenes when Nicholas Ray became ill during the shoot.

Perhaps the purest expression of Ray's belief in the transformative power of love and a classic of its genre, "On Dangerous Ground" is among his most beautiful and moving works. Written by A. I. Bezzerides of "Kiss Me Deadly" fame, the film opens in the harsh urban world of noir, Bernard Herrmann's score flaying nerves as Robert Ryan's coiled cop takes to the mean streets as a semi-psychotic avenging angel ("Why do you make me do it?" the tormented Ryan screams at the latest lowlife he pummels within an inch of his life). It is hard to say what is more stirring: Ryan's forsaken aloneness or Lupino's isolate vulnerability. The daring stylistic and tonal contrasts between the film's two halves, and the theme of the difference between moral and physical sight, intensify the film's tragic irony; in the end, all ground seems dangerous. Lupino actually directed some scenes when Nicholas Ray became ill during the shoot. “I’d love to see more women working as directors and producers. If Hollywood is to remain on the top of the film world, I know one thing for sure —there must be more experimentation with out-of-the-way film subjects”. -Ida Lupino

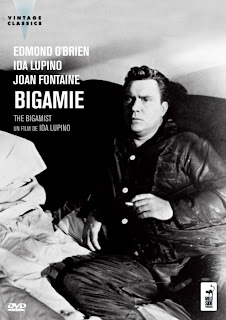

“I’d love to see more women working as directors and producers. If Hollywood is to remain on the top of the film world, I know one thing for sure —there must be more experimentation with out-of-the-way film subjects”. -Ida Lupino “She was a woman director of real personality; her pictures are as tough and quick as those of Samuel Fuller. She was a pioneer for women, especially because she carved out her own territory instead of just waiting to be asked… She proved herself a competent director of second features, and an early discoverer of feminist themes. Thus 'The Bigamist' is not just melodrama, but a critique of woman’s vulnerability.” - David Thomson (The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, 2002)

“She was a woman director of real personality; her pictures are as tough and quick as those of Samuel Fuller. She was a pioneer for women, especially because she carved out her own territory instead of just waiting to be asked… She proved herself a competent director of second features, and an early discoverer of feminist themes. Thus 'The Bigamist' is not just melodrama, but a critique of woman’s vulnerability.” - David Thomson (The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, 2002) “She was so real, offbeat and just lots of fun.” — Cornel Wilde [Actor]

“She was so real, offbeat and just lots of fun.” — Cornel Wilde [Actor]“She wasn’t always easy, but she was worth it.” — Vincent Sherman [Director]

“She is a very warm, very sensitive, very intelligent lady.” —Claire Trevor [Actress]

“She was electric. She never had the popularity she should have had. She was a fine actress. She was beautiful. She had a fabulous figure and was a great director. Maybe she was too strong for those days.” —Sally Forrest [Actress]

“She was electric. She never had the popularity she should have had. She was a fine actress. She was beautiful. She had a fabulous figure and was a great director. Maybe she was too strong for those days.” —Sally Forrest [Actress]